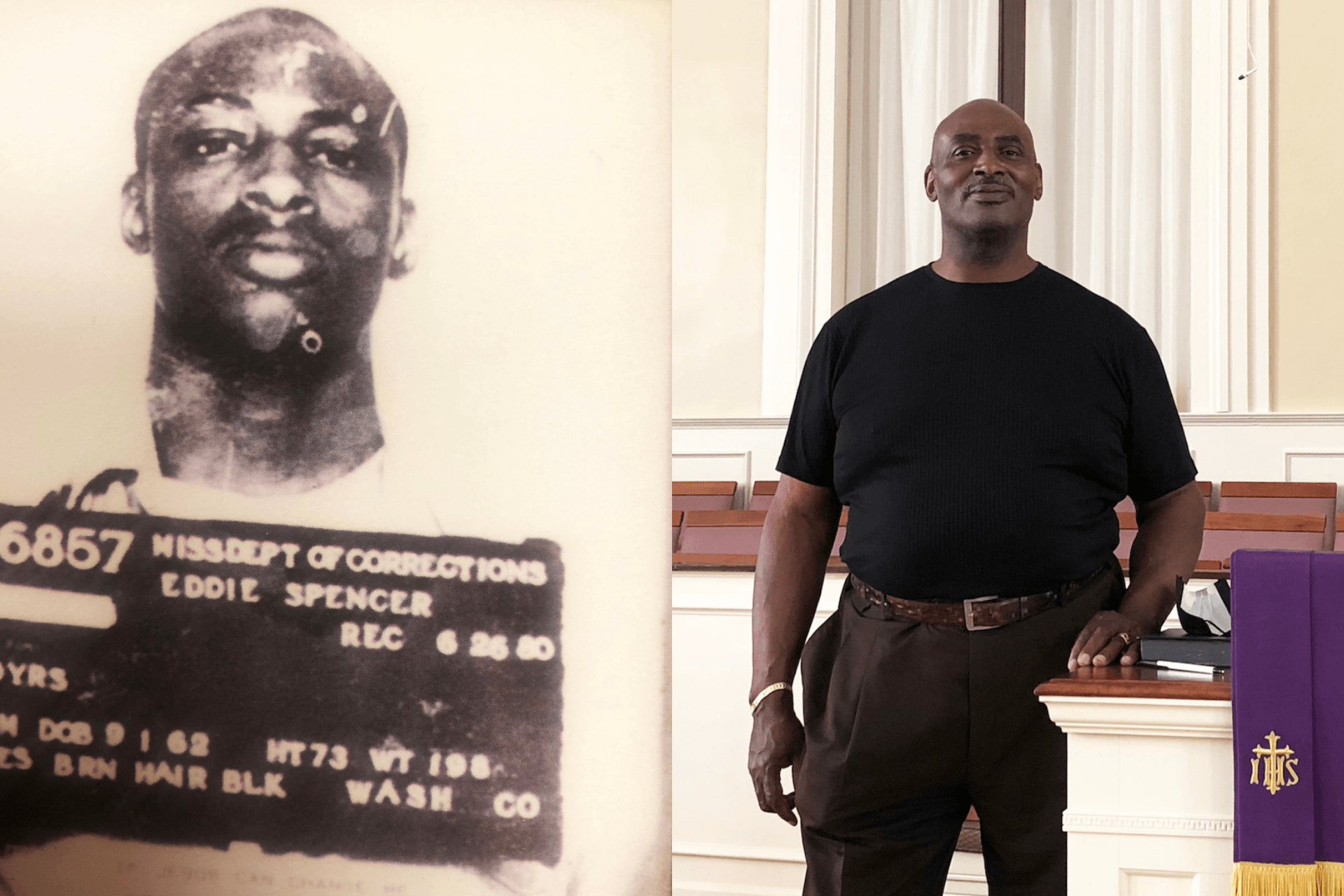

Staring at the death penalty

“I know he’s bad, but he’s a good boy.”

Those words spoken by the mother of a 16-year-old boy echoed through a courtroom in the Mississippi Delta as Eddie Spencer stood before the judge waiting to learn his fate. In 1979, Eddie was facing the possibility of the death penalty as one of his victims was left fighting for his life after being shot.

“Please don’t take my son’s life,” Eddie’s mother pled with tears flowing from her eyes.

“Eddie Spencer, if that man dies you will be facing the death penalty,” responded the judge.

The victim recovered from his injuries and Spencer was headed to Parchman as a young boy to serve the next 10 years of his life for armed robbery and attempted murder.

Eddie’s Early Years

Eddie had spent the first 16 years of his life in and out of jail in the Greenville and Hollandale areas of the Mississippi Delta.

“From the age of 9 through 26, I had spent less than two years outside of jail. I was raised in a very poor, poverty-stricken area,” he said, “and I became angry seeing that we did not have the necessities we needed in life like decent clothes and food.”

In order for Eddie to escape the embarrassment and shame of his family’s circumstances, he turned to crime. It began with stealing out of the neighbors’ yards – anything that he could sell quickly to make a few bucks.

“Then I began going into people’s houses and robbing them,” he said.

He was sent to Columbia Training School in South Central Mississippi.

“The judge said he was sending me there hoping it would change me, but he didn’t realize that going to training school was not punishment. It took away my freedom, but as far as punishment, the living conditions of the training school were better than my living conditions at home,” Eddie said.

Eddie lived in a three-room house with his 11 family members. He shared a bed with his brothers, and they shared the room with their sisters.

“When I got to the training school, I had my own bed,” he said. “For the first time, I was able to have a shower every day. I had three meals every day plus clean linens and clean clothes. That was not punishment to me.”

Eddie’s experience at training school did not change him as the judge had hoped.

“When I came out, I went back to where I had been before. I had not been challenged to look at my life and see what paths I was taking,” Eddie said.

Committing Violent Crimes

At the age of 15, Eddie began to turn to more violent crimes. He robbed people at gunpoint, and he was also introduced to drugs.

“Now I was trying to support a habit,” he said. “I had to get quick money and found myself almost taking a man’s life for $110.”

All of his life Eddie had been told that he would either end up in prison or end up dead. As a 15-year-old boy he had already been shot four times and was doing what he could to survive on the streets. Now, standing before the judge, Eddie was about to go to prison or even be sentenced to death over a $110 armed robbery.

“Here I am standing before the judge and he’s telling me I could get the death penalty.”

Spencer was bound over by the youth court judge and certified as an adult for the crimes with which he was charged. By this time, he had also received a second armed robbery and attempted murder charge.

“When they charged me as an adult the judge looked at me and said, ‘I hope that this right here will wake you up and that you will change before it’s too late,’” Eddie said.

But in Eddie’s young mind it was already too late because now he no longer had the protection of youth court.

Headed to Prison

At age 16 Eddie went to Parchman in 1979 to serve 10 mandatory years.

“I know they say prison is designed to rehabilitate,” he said. “Yes, in my mind and heart I knew I wanted to change, but when I got to prison it was almost like going back to my neighborhood. A majority of the guys that I was in training school with and a lot of the folks from my neighborhood were now in Parchman.”

Eddie was assigned to Camp 22 – the area for kids ages 14-23.

“You’ve got a choice when you go to prison,” Eddie explained. “You can either be an inmate or a convict. An inmate is one who follows the rules and is looking forward to getting out. They have something greater than the present that is motivating them to want to stay focused, want to get out, and to prepare themselves to get out. But a convict is one who just accepts whatever comes their way. They find themselves blending in with their environment – the way they think, their actions, their attitude. When a person looks at you, they almost know you have been to prison because you develop that prison mentality. You become hard.

“The system teaches you that if you are not hard that people will take advantage of you, so you have to have that image. A lot of times that’s not who you are, but that’s what you have to be to survive.”

In the early years of his sentence, Eddie lived the life of a convict. He knew he had to survive.

“Not only here I was at now 17 going to prison, but I also was 17 and couldn’t even read on a second-grade level. At that age I didn’t have any future plans that I could communicate to someone. I would have never dreamed I could be where I am today. I couldn’t see that because there was nothing in my life that was telling me I could be something different. All of my life what I did was live a criminal life.”

A Life Transformed

Three years into his sentence, Eddie began to experience a transformation of his heart. He accepted Jesus Christ as his Savior and began to feel a shift in his life.

“I know a lot of people say that everybody who goes to prison meets God and they have that religious experience,” Eddie said. “I believe that every person when they get locked up has two encounters – one with themselves and one with God, but what you do with that determines your outcome.”

For the next six years behind bars, Eddie’s life began to change.

“The Lord changed my heart. He began to mold me and to break that anger. He broke that stronghold of the prison environment over my life. Yes, it was hard, but it was something that needed to take place in. my life,” he said.

Eddie was befriended by Eugene Wigglesworth, a chaplain.

“He encouraged me. He told me I could be a leader – something I had never thought I could do. He told me I could influence people for the Lord.”

Under the chaplain’s guidance, Eddie began to learn how he could help influence the other men’s lives in a positive way.

“God also placed Lee Holland in my life,” he said. “We are best friends today. He was a white catfish farmer who came once a week to be used by the Lord for Bible study in the prison. He started a Bible study with three of us, and through that I began to learn how to read.”

Eddie left school in the seventh grade when he was asked by the teacher to read aloud.

“I told her I wasn’t going to do it and she said that if I didn’t read out loud that I could leave her classroom,” he said, “so I walked out and never went back. I walked out of school and straight into prison.”

Every Thursday Lee would go into the prison and lead the Bible study with Eddie. He would ask Eddie to read a passage aloud and at first, Eddie said, “No,” but then he began to read aloud.

“I’d stumble over words, and he would never tell me ‘That is wrong.’ He’d always just say, ‘Let me read it,’” Eddie said. “Then I’d go back to my cell and practice the words I had missed.”

Finding Success

Lee encouraged Eddie to get his GED – something Eddie never dreamed of doing. He had been diagnosed with dysgraphia – a disorder that impairs writing ability.

“Not only could I not read, but I couldn’t write. I’d just lock up,” said Eddie. “That was a struggle for me.”

Lee continued to encourage Eddie to enroll in the GED program which he did. Eddie stuck with the coursework and completed the GED in four and a half years.

“I built up the courage to go ahead and take the test,” he said. “When I took that test, I had sweated so bad. I was so nervous. I left there knowing I had flunked it.”

It took two weeks for the results to come back, and during that time Eddie began to doubt himself.

“I began to go back to that old self. I beat myself up so bad. In those moments, when you are on a journey there are always things that are put in your way that cause you to want to look back. If you give in to those moments, it will hinder you from moving forward.”

Eddie was overjoyed when he found out he had passed his test.

“That right there was the best,” he smiled. “That was one thing that I accomplished in life that I didn’t give up on. I was so used to anything that was a threat or that I couldn’t conquer right then and there, I ran from it or took a shortcut. I couldn’t take any shortcuts with that.”

As Eddie neared the end of his sentence, he began traveling with Project Aware – a group that spoke to students about the realities of prison.

“Because of being in my environment, all I knew were curse words. I wasn’t sure that I could speak without using them, but the Lord had begun to change that. I didn’t even realize the change that had taken place,” he said.

Getting Out

Eddie was released in 1988 and granted clemency by Gov. Bill Allain.

“The Lord began to show me that I couldn’t go back to my hometown,” he said. “So I came to Jackson.”

Eddie was 26 and was staying with a couple he met through Prison Fellowship who agreed to let him live with them. He worked odd jobs.

“Coming out, you have to have life skills and learn how to be a productive citizen,” he said. “There are a lot of people who don’t even know what a productive citizen looks like. I had to learn how to communicate and how to respond under pressure. The biggest obstacle was learning how not to react.”

Eddie was able to gather local kids in the neighborhood – some gang members – to help him build the foundations for two Habitat for Humanity Houses. It was through that project that he was introduced to Young Life and asked to lead urban ministry. He was hired and worked with Young Life for the next nine years. He married and had a child, but the marriage did not last.

“That was a hard thing to go through,” he said. “My wife and I wanted different things.”

A New Life

Eddie went on to marry a second time and he and his wife Betty are celebrating 25 years of marriage this year. And Eddie has three children.

Today, Eddie serves as the pastor of Alta Woods United Methodist Church in Jackson and Mt. Salem United Methodist Church in Terry. He’s written two books with co-author LaFon Walcott Burrow, Inmate 46857 and Put Out the Fire. He walks quietly and leads others to Jesus Christ – just as Chaplain Wigglesworth told him he could do.

“If you look at my record, you’d say there was no hope for that man. I’m grateful and humbled. Some people have a very narrow view of an ex-inmate, but I say that we can use that to give them something to see that can maybe change their minds. Every person on the earth has received second, third, and fourth chances,” he said. “If a person has proven themselves and shown that a second chance could benefit them, why would we not walk with them?”