Mandatory minimum laws lead to sentences that don’t match the crime

Life in prison for seven boxes of Sudafed? It just doesn’t make sense.

Mississippi’s habitual enhancement, which applies harsh mandatory minimum sentences to those with previous criminal records, even for relatively minor offenses creates unfair outcomes.

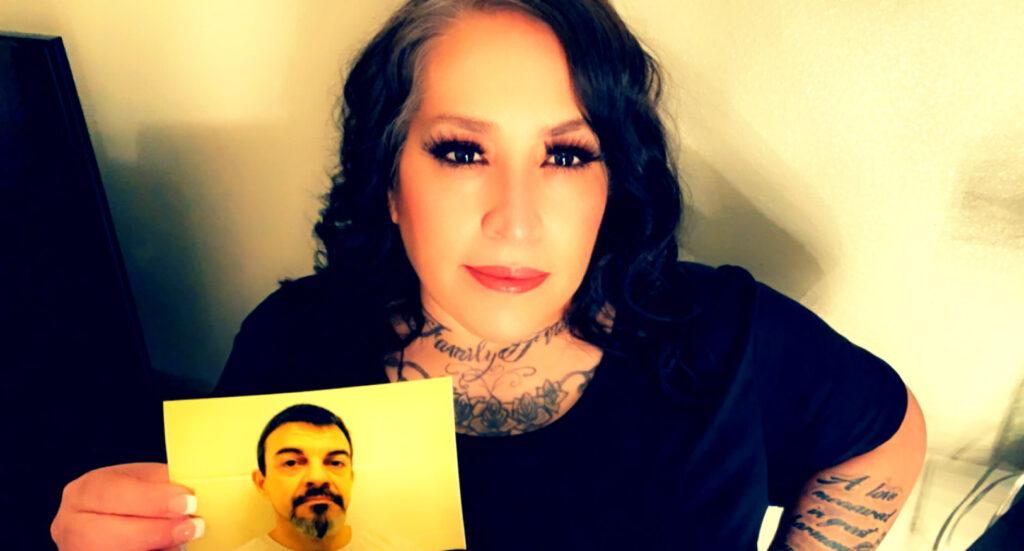

James Vardaman and his family are all too familiar with those outcomes. Vardaman’s third conviction because of his drug addiction qualified him to be sentenced as a habitual offender and since one of his prior convictions was a violent offense, sentencing as habitual offender meant life without the possibility of parole. Additionally, because his third conviction was for two offenses, he received two life sentences.

At the time of his arrest, Vardaman had served his time for his previous offense and had begun to turn his life around. He had found the dignity of work as a welder and was working with a crew building one of the local hospitals when the demon of addiction reared its head in his life yet again. He was arrested in Brandon where he was charged with having a precursor, seven empty boxes of Sudafed, and with conspiracy to cook methamphetamine.

Sixteen months after his arrest, Vardaman, sitting in a Rankin County courtroom, was convicted as a violent habitual offender, and sentenced to two life terms in prison – all for methamphetamine.

He is 15 years into his two life sentences.

“I used to be a taxpaying citizen with a good job, and it doesn’t seem fair to ask taxpayers to lock up people like me,” he said. “I served my time for my two previous convictions and it’s just not right to serve two life sentences for this.”

The impacts of his harsh sentence extend far beyond the four walls of his prison cell.

Vardaman’s wife Christina, now living in Texas with the youngest two of their six children, is doing all she can to hold the family together, and the introduction of COVID means that they have not seen Vardaman in over a year.

“It’s hard,” she said. “It’s been very hard on the kids. I don’t think they have built the bond with him that most kids have with their parents because we haven’t been able to see him.”

The habitual offender law ties the hands of the state’s judges by preventing them from exercising discretion and considering the facts of the case. Further, it applies sentences that can be grossly disproportionate to the underlying conduct. In recent years, states have moved to eliminate mandatory minimums to allow for individualized sentences that restore the notion of a punishment that fits the crime.

According to Grading Justice, Mississippi scored a “D” for its mandatory minimum sentencing laws. Lawmakers can take steps forward to improve that grade by making sure that mandatory minimums don’t apply to low-level conduct. Harsh sentences have a place and should be applied for particularly heinous crimes and a judge should have the ability to make that decision after hearing the case. Currently, Mississippi judges have the flexibility to suspend sentences up to 100 percent in their discretion, except in cases of individuals charged with habitual offenses.

“A judge should be able to determine the appropriate sentence instead of being forced to apply one that doesn’t always fit the crime,” said J. Robertson, Fellow on Criminal Justice Reform at Empower Mississippi. “No two crimes are the same and mandatory minimum sentences don’t make sense. We should be looking at intervention programs rather than imposing long, harsh sentences for minor crimes.”

Robertson noted that there was a push in 1994 under the Clinton-Biden Crime Bill to get tough on crime, but the nonsensical way in which it was implemented has harmed many Mississippians. It’s taken them away from their families, out of productive work, and drained Mississippi taxpayers.

“There is no science to say that this approach improves crime rates,” Robertson said. “That’s why most states are moving away from mandatory sentences.”

Placing the decision in the judge’s hands makes more sense.

“Judges are more connected with their communities than lawmakers in Jackson,” Robertson said, “and oftentimes they know these people and know the story. Eliminating a mandatory minimum sentence isn’t eliminating the sentence completely. It’s allowing the judge to apply an appropriate sentence.”