How the Parole Board makes decisions

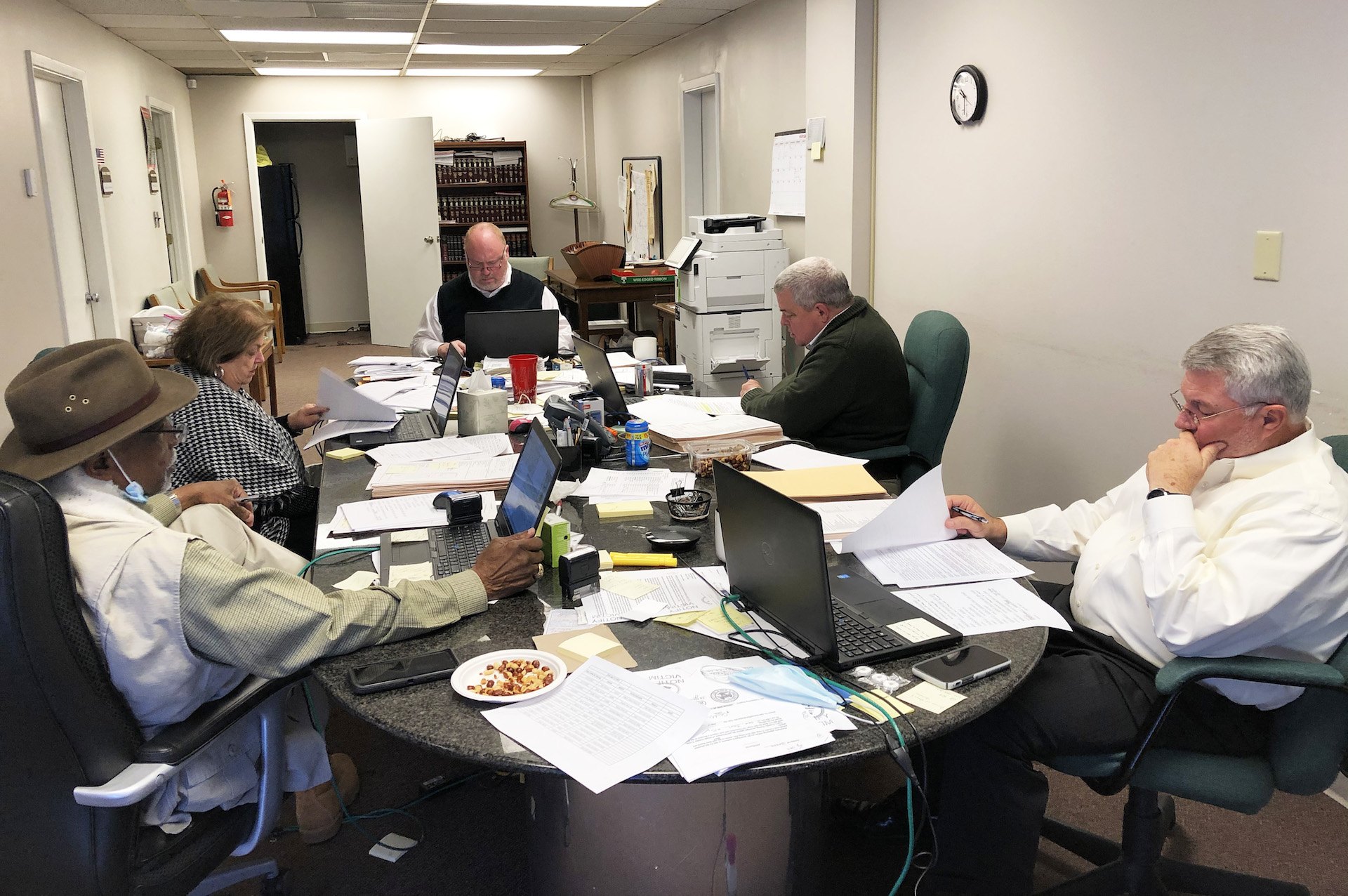

It’s a busy day at the Mississippi Parole Board. Cases are stacked up and the phone is ringing.

“The parole board reviews cases every day,” said Steve Pickett, chairman of the board.

The cases heard by the board include regular parole hearings for those who are becoming eligible after serving 25 percent of their sentence, parole revocation, and life sentences prior to 1996.

“There are about 600 people serving life sentences prior to 1996,” Pickett said. “We see a couple dozen lifers per week.”

Paroles are rare when it comes to those serving life sentences because those are the toughest decisions.

“We visit with victims and proponents every Monday afternoon,” he added. “The parole board is extremely accessible.”

The board is made up of five members appointed by the governor. They include Pickett who has served for nine years, Betty Lou Jones who has served for 13 years, Nehemiah Flowers who has served for 8 years, Jim Cooper who has served for one year, and Anthony Smith who has also served for one year.

“It’s a full-time job,” said Jim Cooper. “I think I was most surprised by the workload. On a slow month, we make decisions on about 500 people, and on a busy month that number is anywhere between 800 and 900 people.”

Last year, the board looked at roughly 6,200 cases and denied parole to 1,714 people. The biggest factor in determining parole is public safety.

“That is the number one thing we consider,” said Pickett. “It’s our duty to work in the state’s best interest.”

“We look to see if they are likely to get out and harm someone else,” Cooper added. “If I feel like they are a danger to the public, I will vote not to parole. If someone is a rule violator in prison, they are probably going to come out in public and be a rule violator. You look at someone’s history and if they’ve got a lot of violence in their background. Prison doesn’t do a great job of making them nonviolent.”

The board hears from all involved in the case before rendering a decision.

“Victim input is very important to us,” Pickett noted.

“That carries a lot of weight,” Cooper added. “We look at the history. If we are going to parole someone back to the town where the crime happened, and we have a victim in the town who is scared to death that is something we take very seriously.”

The decisions made by the board are not quick. They require input, thought, and deep review.

“For each one of these cases, we look at it on the offender track on our computer. The offender track has all the pertinent information that we have to go on. We look at rule violations, past history, and how they have behaved in prison,” said Cooper. “We look for family support. We consider whether or not they have a good job opportunity and whether or not they have a good place to live because their address has to be approved.”

Pickett agreed.

“There is a shortage of halfway houses in Mississippi which makes it difficult for some people who don’t have any place to go,” Pickett said. “We look at their re-entry plan to determine how successful they will be on parole.

“Setting someone up for failure and putting the public at risk by setting someone free without a good re-entry plan is not in the state’s best interest.”

Talking with those who are incarcerated, their families, law enforcement, judges, and district attorneys, the board is able to get a fairly clear picture of the person. They are able to look at classes and things that someone who has been incarcerated has taken to improve themselves.

“We talk to them and find out about what they’ve been doing while in prison. If they can convince us that they are trying to improve themselves, then we are likely to give them a chance,” said Cooper.

The board has become well-versed in the lines that those who are incarcerated may try to give or in being able to spot an actor.

“People lie to us all day long,” Cooper laughed. “We try to give parental type guidance, but ultimately they are on their own to succeed or not. We try to give them every opportunity, but we don’t have many opportunities to give.”

Limited opportunities and a large prison population make it more difficult for those who want to improve their lives.

“When you take a state facility that has roughly 3,200 to 4,000 prisoners under one roof, what kind of environment and productivity are we setting the stage for? There is a need for programming, job training, and alcohol and drug treatment. The smaller the facility, the more successful it is because you are able to give more attention,” Pickett said. “My background is that I worked with Sheriff McMillan in Hinds County and we operated the county farm. We had 400 county prisoners at the work center. It’s like Commissioner Cain says. If you provide good food, access to religious activity, good visitation, and a purpose-driven day with having a task that introduces folks who are incarcerated to people they never would have met, you’re providing more opportunities for success. Our inmates worked with the animal rescue league, the zoo, the food network, Stewpot, and other organizations. Those places actually became places of employment for inmates who had worked there during their sentences.

“It’s important to have something to do with your time other than set about to physically destroy the building or harm someone else.”

Cooper noted that the board hears more of the failures than they do of the successes because those who go on to be successful don’t come back before the board.

“It’s a wonderful feeling when we do hear those success stories. It’s always a good thing to hear of people who got out of a predicament and went on to do something good with their life,” said Cooper.