How testing killed creativity

There’s a fire that has burned inside of Khrysten Glass for as long as she can remember. It’s a passion to educate children.

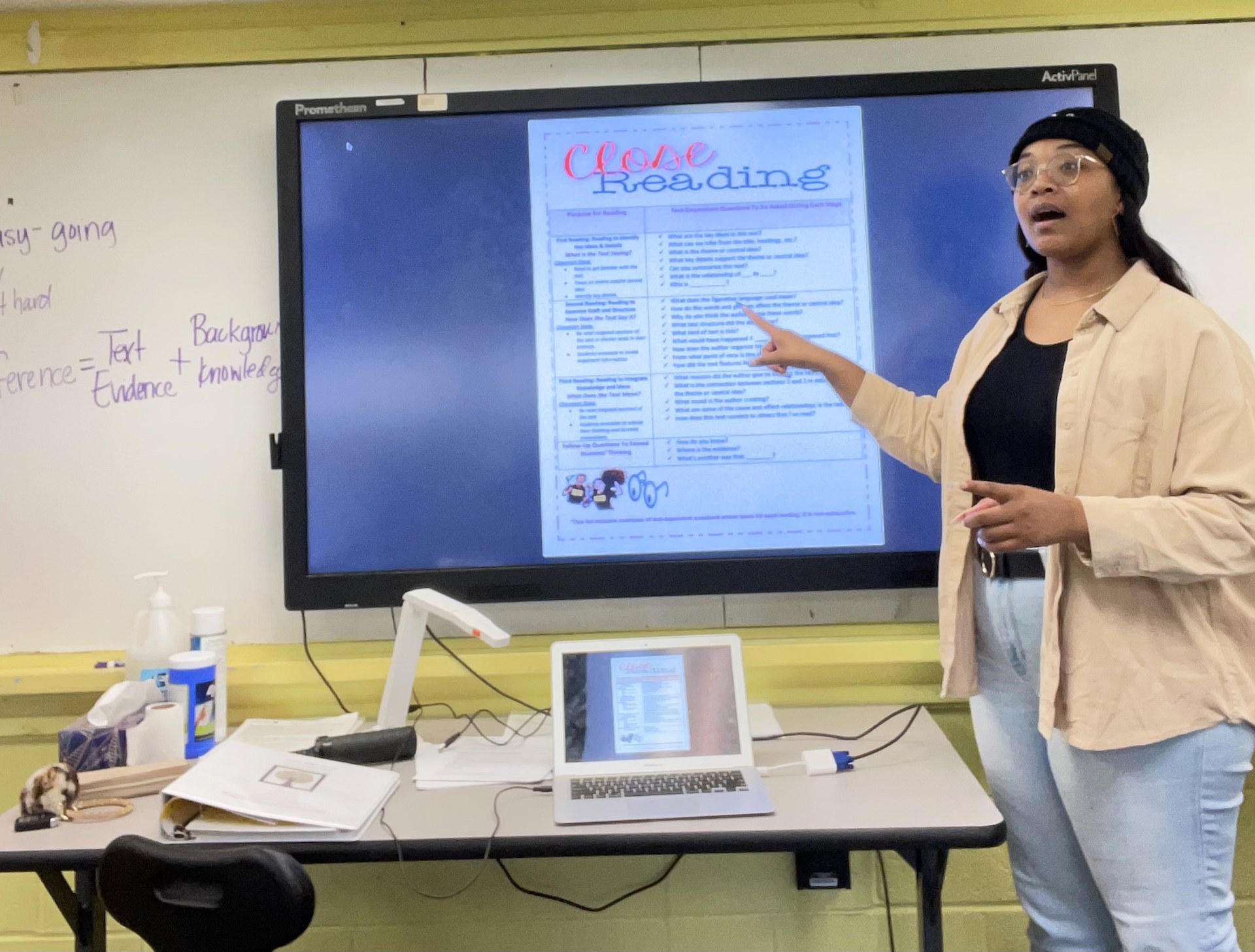

The young teacher is in her fourth year at Nichols Middle School in Canton and has already been named Teacher of the Year during her tenure.

Khrysten always knew she wanted to return to the city of Canton – her hometown—to give back to the community. Today, she walks the halls of her school worried. She’s worried about her students, not about their test scores, but worried about their safety, worried about their future, worried about their home life, worried about their health. While these are the concerns that tug at Khrysten’s heart as an educator, education bureaucrats say Khyrsten should be more concerned with state test scores, showing growth in the classroom, and moving her students on to the next grade – sometimes when they are not ready.

“Education has become all about the accountability matrix,” Khrysten said. “It’s all about our scores and the data we can show. It’s not about educating the whole child and meeting them where they are which is why I got into education in the first place.”

Teachers like Khrysten are stifled. There’s no room for creativity in the classroom – no room for much of anything in the classroom except testing or test prep.

“Every day we are doing something related to testing in the classroom,” she said.

It’s not because Khrysten and her students are working to get ahead on their test prep, but instead because it is required that teachers teach and prep students every day for the test.

“It’s hard,” she said. “I’ve found myself in a ‘teacher funk’ because this field is not what I expected. In college, we get excited and are prepared to go into the classroom ready to teach children and meet them where they are, but that’s not what the day-to-day classroom teaching is like in reality. We must deliver a percentage of growth, and while administration and MDE is looking at data and numbers, we, as teachers, are looking at the whole child. There’s so much more to our students than just a test.”

Khrysten said she believes that the testing that is performed is not an accurate snapshot of the child.

“It doesn’t give you a picture of who that child is and what they are capable of. It also isn’t for me as a teacher. All of the testing we do is for the people above me, and they have no idea what it is like to be in a community like mine,” she said. “I understand the intention of testing, but the execution of it is poor.”

In an area where most of her students come from single-parent, low-income households, Khrysten’s concerns for her students are much more than their test scores.

“When you have a student who has to get himself up and his three siblings, get them dressed, get to school and do his work, then he has to make sure everyone gets home and hope that they have something to eat in the house because they are on government assistance and Mom is working two jobs and isn’t able to be there, do you think that child’s first concern is a state test? Absolutely not. How is he supposed to focus on a test?” Khrysten emphasized. “These children are living real world issues. We have kids who are being shot and murdered in our community.”

For Khrysten, as a teacher, the frustration goes deeper because students are being passed on to the next grade.

“We have kids who need to stay and learn the things that are being taught, but because of the testing setup, that isn’t happening,” she said. “They are being passed on, and the kids know that, so they aren’t motivated to do any better.”

As Khrysten looks to the future of education in Mississippi, she says we must “begin with the end in mind.”

“If you want citizens in our state to be productive members of society, then you have to teach them how to do that, and that’s supposed to be my job. That’s what I got into teaching to do. I’m supposed to teach them life skills and prepare them for where they go after high school, but I need the freedom to do that and with test after test there is no time for that kind of instruction.

“Where does it end? It’s disheartening for me, and that fire inside of me has begun to grow dim.”