Charter schools win lawsuit. What does it mean?

This week, charter schools in Mississippi were victorious after a Hinds County judge found state law requiring local ad valorem tax dollars to follow charter students constitutional.

Mississippi is one of 43 states with laws allowing public charter schools to open. Charter schools are free, public schools with some freedom from traditional regulations. They are run by independent boards instead of elected local school boards and answer to an authorizer that oversees their charter agreement. The first charter school in the nation opened in Minnesota in 1992 as a laboratory of innovation for the public sector, and since then thousands of these “schools of choice” have materialized across the nation.

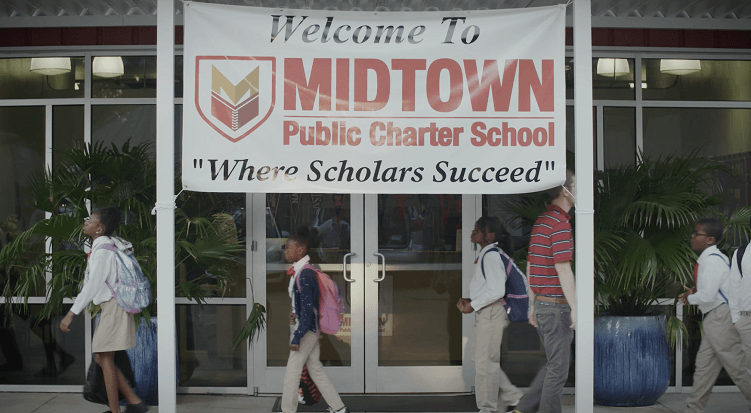

The Mississippi Charter Schools Act passed in 2013, and today, 5 schools have been approved by the authorizer board. Approximately 1,000 children attend three middle schools in Jackson, while two more schools – another in Jackson and one in Clarksdale – plan to open this year. These schools are providing more options to families who need them, and all schools have waiting lists.

A Challenge to the Charter Law

In July 2016, a group of Jackson parents represented by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) filed a lawsuit against the state for enacting a charter law that was “unconstitutional.” They challenged the provision of the law requiring local ad valorem tax dollars to follow students to charter schools, claiming this violated Sections 206 and 208 of the Mississippi Constitution.

Section 206 states that a county or district may levy a tax “to maintain its schools.” SPLC submitted that the Legislature could not require a school district to share its ad valorem taxes as a result, citing the state supreme court decision in Pascagoula School District v. Tucker as precedent that precluded taxes from being transferred to schools outside the district’s control.

Mississippi’s original law allowed charter schools to open only in D or F-rated districts; the law was later amended to allow students from nearby C, D, or F-rated districts to travel across district lines to attend a charter school.

SPLC also argued that the charter law failed to comply with Section 208 which prohibits funds from being appropriated toward any school “not conducted as a free school.” They posited that a “free school” is one overseen by state and district superintendents.

A Long-Awaited Verdict

After over a year and a half since the initial challenge, the Court found that both arguments did not prove the charter law unconstitutional “beyond a reasonable doubt”.

The Court denied that Pascagoula was relevant precedent since it dealt with the question of whether districts could be forced to share their taxes with other districts without any benefit to local students. In the case of charter schools, local money provides a clear benefit to local students because it follows them to their school of choice, wherever it is. Additionally, as defendants argued, state law already requires local tax dollars to follow some students who are district transfers or attend agricultural high schools and alternative school programs.

Regarding Section 208, the Court found that the plaintiffs’ definition of a “free school” was invalid. The plainest interpretation of constitutional language simply requires that charter schools not charge tuition, which they do not. They are free to those who wish to attend and can get in through a lottery.

Moving Forward

SPLC says it will appeal the judge’s decision to the state supreme court. The national organization’s stated mission is to fight “hate and bigotry” and to seek “justice for the most vulnerable members of our society,” although it’s unclear how crippling or removing altogether an option many needy families are happy with fulfills their mission.

Had SPLC won the lawsuit, charter schools would have been forced to educate their students without approximately 35 percent of per student funding for public school students. Many have wondered if they could remain open under such circumstances. New charter operators would have been discouraged from coming to the state to offer more options in more communities. Families in charter schools and those waiting to get in would have seen school leaders scrambling to shift resources, cutting services, and spending more time raising private money.

Thanks to the Court’s ruling last Tuesday, the future for charter schools in Mississippi remains bright.